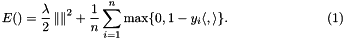

$ are the *ground truth labels* of the corresponding example vectors. The fit quality is measured by a loss function* which, in standard SVMs, is the *hinge loss*:

\[ ( ,) = , 1 - y_i ,\}. \]

Note that the hinge loss is zero only if the score $ ,$ is at least 1 or at most -1, depending on the label $y_i$.

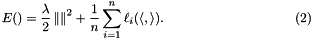

Fitting the training data is usually insufficient. In order for the scoring function *generalize to future data* as well, it is usually preferable to trade off the fitting accuracy with the *regularity* of the learned scoring function $ , $. Regularity in the standard formulation is measured by the norm of the parameter vector $\|\|^2$ (see Advanced SVM topics). Averaging the loss on all training samples and adding to it the regularizer weighed by a parameter $$ yields the *regularized loss objective*

Note that this objective function is *convex*, so that there exists a single global optimum.

The scoring function $ , $ considered so far has been linear and unbiased. Adding a bias discusses how a bias term can be added to the SVM and Non-linear SVMs and feature maps shows how non-linear SVMs can be reduced to the linear case by computing suitable feature maps.

Learning shows how VLFeat can be used to learn an SVM by minimizing $E()$.

Learning

Learning an SVM amounts to finding the minimizer $^*$ of the cost function $E()$. While there are dozens of methods that can be used to do so, VLFeat implements two large scale methods, designed to work with linear SVMs (see Non-linear SVMs and feature maps to go beyond linear):

Using these solvers is exemplified in Getting started.

Adding a bias

It is common to add to the SVM scoring function a *bias term* $b$, and to consider the score $ , + b$. In practice the bias term can be crucial to fit the training data optimally, as there is no reason why the inner products $ , $ should be naturally centered at zero.

Some SVM learning algorithms can estimate both $$ and $b$ directly. However, other algorithms such as SGD and SDCA cannot. In this case, a simple workaround is to add a constant component $B > 0$ (we call this constant the *bias multiplier*) to the data, i.e. consider the extended data vectors: \[ = {bmatrix} \ B {bmatrix}, = {bmatrix} \ w_b {bmatrix}. \] In this manner the scoring function incorporates implicitly a bias $b = B w_b$: \[ , = , + B w_b. \]

The disadvantage of this reduction is that the term $w_b^2$ becomes part of the SVM regularizer, which shrinks the bias $b$ towards zero. This effect can be alleviated by making $B$ sufficiently large, because in this case $\|\|^2 w_b^2$ and the shrinking effect is negligible.

Unfortunately, making $B$ too large makes the problem numerically unbalanced, so a reasonable trade-off between shrinkage and stability is generally sought. Typically, a good trade-off is obtained by normalizing the data to have unitary Euclidean norm and then choosing $B [1, 10]$.

Specific implementations of SGD and SDCA may provide explicit support to learn the bias in this manner, but it is important to understand the implications on speed and accuracy of the learning if this is done.

Non-linear SVMs and feature maps

So far only linear scoring function $ , $ have been considered. Implicitly, however, this assumes that the objects to be classified (e.g. images) have been encoded as vectors $$ in a way that makes linear classification possible. This encoding step can be made explicit by introducing the *feature map* $() ^d$. Including the feature map yields a scoring function non-linear* in $$: \[ {X} (), . \] The nature of the input space ${X}$ can be arbitrary and might not have a vector space structure at all.

The representation or encoding captures a notion of *similarity* between objects: if two vectors $()$ and $()$ are similar, then their scores will also be similar. Note that choosing a feature map amounts to incorporating this information in the model prior* to learning.

The relation of feature maps to similarity functions is formalized by the notion of a *kernel*, a positive definite function $K(,')$ measuring the similarity of a pair of objects. A feature map defines a kernel by

\[ K(,') = (),(') . \]

Viceversa, any kernel function can be represented by a feature map in this manner, establishing an equivalence.

So far, all solvers in VLFeat assume that the feature map $()$ can be explicitly computed. Although classically kernels were introduced to generalize solvers to non-linear SVMs for which a feature map *cannot* be computed (e.g. for a Gaussian kernel the feature map is infinite dimensional), in practice using explicit feature representations allow to use much faster solvers, so it makes sense to *reverse* this process.

This page discusses advanced SVM topics. For an introduction to SVMs, please refer to Support Vector Machines (SVM) and SVM fundamentals.

Loss functions

The SVM formulation given in SVM fundamentals uses the hinge loss, which is only one of a variety of loss functions that are often used for SVMs. More in general, one can consider the objective

where the loss $(z)$ is a convex function of the scalar variable $z$. Losses differ by: (i) their purpose (some are suitable for classification, other for regression), (ii) their smoothness (which usually affects how quickly the SVM objective function can be minimized), and (iii) their statistical interpretation (for example the logistic loss can be used to learn logistic models).

Concrete examples are the:

| Name | Loss $(z)$ | Description |

| Hinge | $\{0, 1-y_i z |